Report Also Shows Potential Increase in Health-Damaging Air Pollutants from Industry Growing Because of Fracking Boom

Washington D.C. – Fueled by the fracking boom, oil and gas-related industries across the U.S. are planning to build 157 new or expanded plants and expand drilling over the next five years. This could release as much greenhouse gas pollution as 50 new coal-fired power plants, state and federal records show.

A new report by the Environmental Integrity Project (EIP) reveals that companies that extract or refine oil and gas, export liquefied natural gas, or manufacture petrochemicals, plastics, or fertilizers, have final permits or applications to release up to 227 million tons of additional greenhouse gas pollution by the end of 2025, with 36 million tons of this from expanded drilling.

This potential increase of 227 million tons would represent a 30 percent rise over the 764 million tons emitted by the industry in 2018, the most recent available data, according to permits and records reviewed by EIP.

“Oil and gas production and petrochemical manufacturing are responsible for most of the growth in greenhouse gas emissions today,” said Eric Schaeffer, Executive Director of the Environmental Integrity Project. “Unfortunately, the permits being issued by states and EPA for the largest projects do not include cost-effective methods for controlling greenhouse gas pollution, even though this is required by the federal Clean Air Act. Unless you think global warming is a hoax, that needs to change.”

EIP’s estimate includes emissions from oil and gas fields, based on the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s latest predictions of future output, and from greenhouse gas limits in Clean Air Act permits issued to 157 of the largest projects. Actual emissions growth from the oil, gas and petrochemical sectors is likely to be much higher than 227 million tons by 2025 because this estimate does not include thousands of smaller projects that are not required to obtain permits that limit greenhouse gases.

In addition to looking at future emissions, EIP’s report, “Greenhouse Gases from Oil, Gas, and Petrochemical Production,” also looks backward. The report documents an 8 percent, or 57 million ton, rise in greenhouse gases from the industry from 2016 to 2018, the most recent available year for emissions data.

The sectors with the biggest total increases were oil and gas drilling (which experienced a rise of 26 percent, or 26 million tons, over this time period); and other petroleum and natural gas systems, including pipelines and compressor stations, which saw a 9 million ton, or 5 percent, increase from 2016 to 2018.

“The US is already struggling to meet climate commitments and transition to a low-carbon future,” said Courtney Bernhardt, Research Director at the Environmental Integrity Project. “This analysis shows that we’re heading in the wrong direction and really need to slow emissions growth from the oil, gas, and petrochemical industries.”

Beyond just greenhouse gases, the 157 oil and gas related projects planned by 2025 would also likely increase pollutants that are immediately harmful to public health. According to their permit documents, the facilities could emit every year up to 119,000 tons of volatile organic compounds, which are a component of smog; 11,100 tons of fine particles that contribute to asthma and heart attacks; 8,800 tons of sulfur dioxide, which damages the lungs; and 47,200 tons of nitrogen oxides, which feed fish killing “dead zones” in waterways.

Among other key findings of EIP’s report, “Greenhouse Gases from Oil, Gas and Petrochemical Production,” are the following:

- About half (76 of the 157) of the future projects are planned for Texas or Louisiana. These new or expanded plants could produce 145 million tons of greenhouse gases annually, accounting for roughly 75 percent of the expected increases from new oil and gas-related projects across in the U.S.

- The largest potential growth in greenhouse gas emissions could come from export of liquefied natural gas (LNG). Eight LNG terminals in the U.S. released seven million tons of greenhouse gases in 2018, which was a more than 10-fold increase over 2016. An additional 18 new LNG export sea terminals and one inland facility are planned by 2025 that could emit up to 80 million more tons annually – a potential 100-fold increase over a decade.

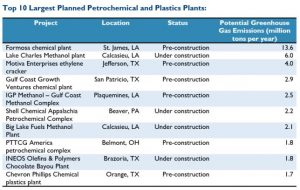

- Petrochemical and plastics plants released 80 million tons of greenhouse gases in 2018. Proposed expansions and new plants could raise emissions by an another 64 million tons annually – a potential 80 percent increase – by the end of 2025.

- Ammonia fertilizer plants, which use natural gas as a primary ingredient, released 40 million tons of greenhouse gases in 2018, up from 31 million tons in 2016. That total could expand by another third, to 53 million tons, within five years.

One major source of emissions in West Texas is venting or flaring of gas from oil and gas facilities. Average daily flaring rates in the Permian Basin climbed past 700 million cubic feet per day in 2019, a nearly 21-fold increase from seven years earlier and more than enough gas needed to power every home in Texas.

Petrochemical and plastics plants are also expanding rapidly. The largest projects are listed below:

For a database listing all of the projects by state and their emissions, click here.

The EIP report makes the following recommendations to address growing air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from the oil and gas sector:

1) State environmental agencies and EPA should issue stronger air pollution control permits that include cost-effective measures to minimize greenhouse gas pollution.

2) Congress and the states should fund EPA and state environmental agencies sufficiently so they can provide appropriate monitoring, oversight and environmental enforcement, which is often not happening today.

3) EPA needs to require much more accurate methods to monitor emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants from leaking tanks, oil and gas processing equipment, and flares with poor combustion efficiency.

4) Air pollution control permits should require fenceline monitoring to help identify and reduce dangerous concentrations of toxic gases before they cross plant boundaries into nearby communities.

The Environmental Integrity Project is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization based in Washington, D.C., and Austin, Texas, that protects public health and the environment by investigating polluters, holding them accountable under the law, and strengthening public policy.

Media contact: Tom Pelton, Environmental Integrity Project, (443) 510-2574 or tpelton@environmentalintegrity.org